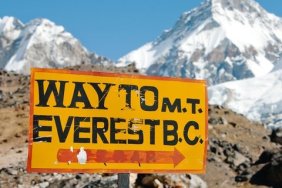

When Army veteran Chad Jukes conquered Mount Everest earlier this eyar, he made international headlines as the second amputee survivor to climb the highest mountain earth with the past five days.

Jukes made the climb with a group called No Barriers, whose mission is to get veterans into the outdoors and raise awareness about PTSD and veteran suicides. On Thursday, Jukes shared his story with attendees at the Outdoor Retailer convention in Salt Lake City at the Marmot booth.

“I have personally lived with PTSD, have personally experienced what it’s like to come home from war and not know your place and not be able to really handle what you went through,” Jukes said. “I know a lot of other people suffer very severely from that.”

In 2006, while deployed in Iraq as a staff sergeant on convoy security operations in Northern Iraq, the truck he was riding in ran over an anti-tank mine buried in a pothole. Jukes suffered extreme damage to his foot and was hospitalized for two months. It was during that time that he contracted an infection and was faced with a decision to amputee or rebuild his heals.

The first thing on Jukes’ mind, who had been a sport climber before the accident, was whether he could climb with a prosthesis.

“When I heard about amputation, I thought why would I cut my foot off, that’s crazy. But when he got on-line to look into amputee climbing, I found a guy who said he would definitely be able to climb and be able to climb well,” Jukes said. “So very quickly I decided to have my leg chopped off. It only took a couple of days.”

To prepare for the trip, Jukes climbed Mount Rainier and trained during the off-season. In early April they headed to Nepal and began their climb. It was on the mountain that Jukes received some hard news. A friend of his, a fellow veteran, had recently committed suicide.

“That was a really hard thing for me to process and deal with, but it really drove home my mission on the mountain and gave me a new found resolve to get to the top,” he said.

On May 24, he successfully summited up the northeast ridge. But as is often the case on Everest, summiting was only half the battle. On the way down, Jukes discovered his oxygen line had been damaged and leaking air, so that he ran out of supplemental oxygen before reaching base camp, which caused his physical condition to debilitate.

Then after regrouping at a high elevation camp not usually intended for sleeping, the team was able to continue their descend the next morning, but this time in the midst of blizzard that saw driving snow and 70 mph winds. He said at some points the team was crawling on their hands on knees – anything to avoid getting blown off the mountain. But they worked together, huddling behind boulders at times when conditions worsened.

“There were times when you couldn’t take a step because if you lifted one foot up you would get blown over,” he said. “But we got through it and pushed each other to survive.”

Asked recently whether climbing Everest meant that he would retire from mountain climbing, Jukes looked incredulous. “What? Uh, no,” he said. “Climbing is what I do.”

Photo credit: LiveOutdoors (featured) ArmyTimes (insert)